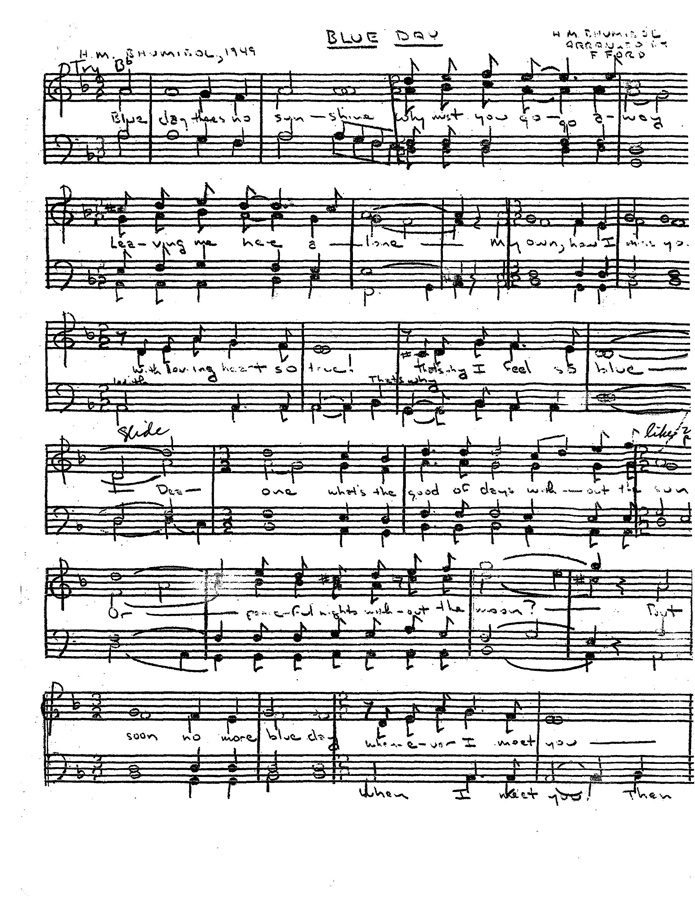

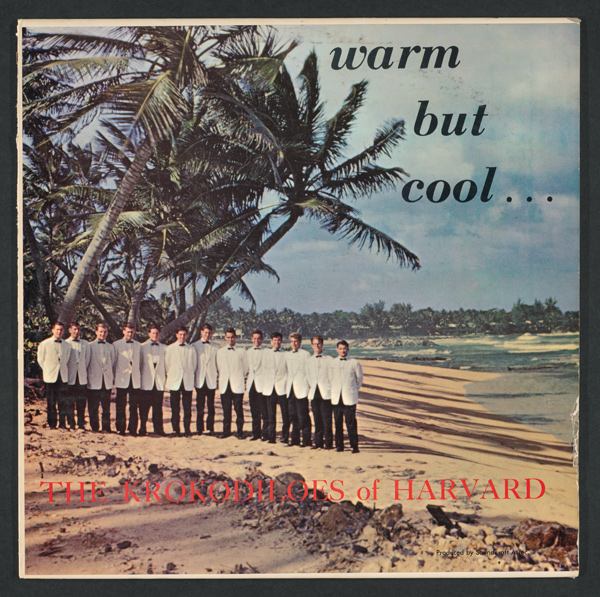

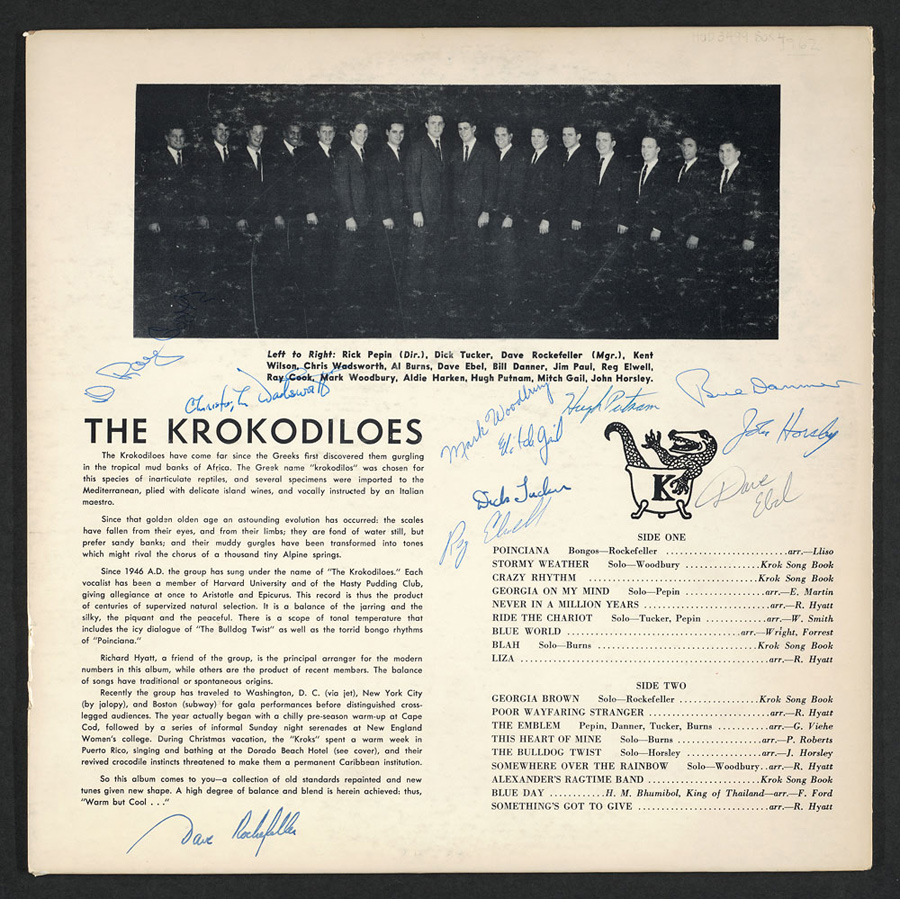

Fred Ford, conductor of the Harvard Krokodiloes of 1960, writes:

“In advance of the upcoming HGC Far Eastern Tour, Prof. Elliot Forbes, conductor, had arranged one or more versions of local songs for each country we would visit. What El received from Thailand was a melody composed by King Bhumibol himself. It was hard to decipher the tune, the rhythm and phrasing, but it was, El understood, the King’s version of Benny Goodman’s style. (The King was himself an amateur clarinetist and a Goodman fan.) El called me in to his office. At the time I was his HGC assistant conductor, and had just finished my senior year as Kroks director. El said he felt I might have better luck deciphering and arranging Blue Day which he felt was more in my style. And so I parsed and examined that melody, modified the meters and expanded it to four parts.”

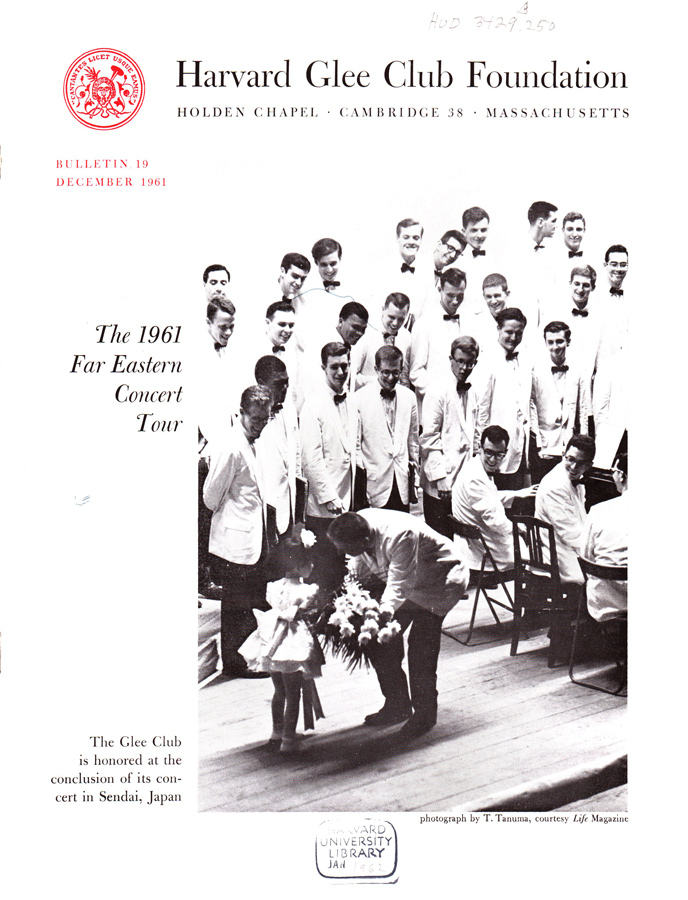

The first rehearsal was in the back of an Air France plane while flying over Chinese airspace, not open to US air carriers at the time, on the way to Bangkok.

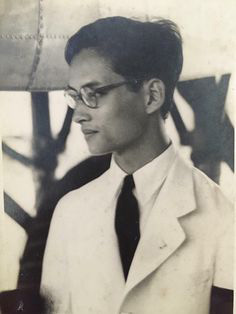

They performed it on August 1, 1961 at Culture Hall in Bangkok for a command performance before the King and Queen. The Harvard Glee Club Foundation reported:

“This was our first experience with high protocol, and there was a good deal of scurrying about to be sure that reception lines, roped off areas, introduction of the Glee Club, the length of the concert, the number of encores, etc., were all in perfect order. The King is something of a composer himself, as well as having a strong penchant for jazz, and a small group of singers had made an arrangement of one of his songs, ‘Blue Day’, which was sung as the first encore.

El Forbes’s wife Kay reported that seated behind the royal box she saw “the ghost of a smile flicker” across the King’s face on hearing the performance and added that “Apparently, His Majesty is not allowed to smile, in public, so this was an achievement.”“

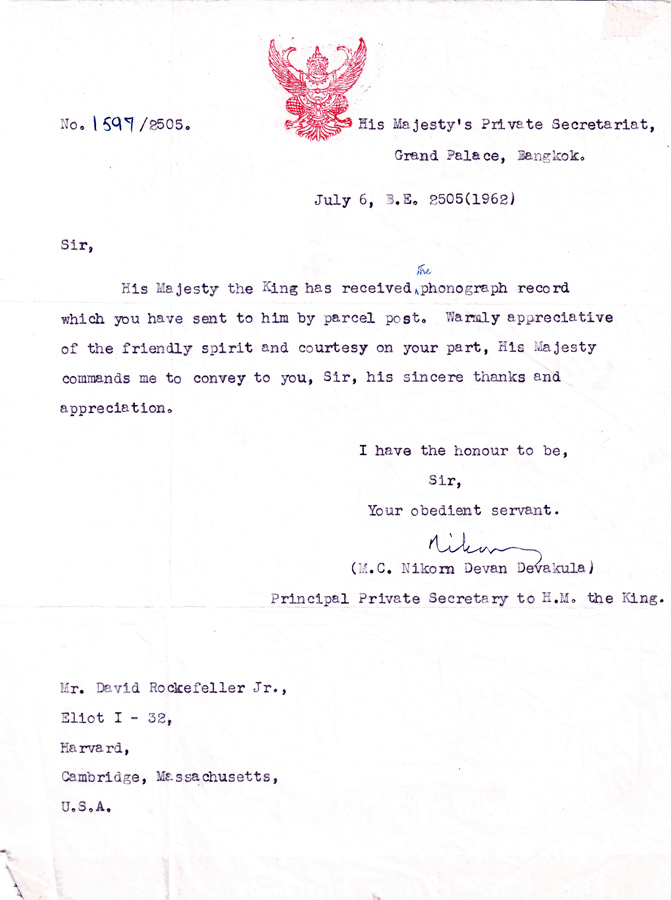

The Krokodiloes who sang for the King that night were Ray Cook ’64, Rick Pepin ’62, Hugh Putnam ‘63, Bruce Carr ‘60, David Ebel ’62, Fred Ford ’60, David Livingston ’61, Vic Tom ’61, Al Burns ’63, David Rockefeller, Jr. ‘63 and John Ryden ’61.

The relationship with the Royal Family continued in the summer of 2004 when the Kroks sang Blue Day for King Bhumibol’s eldest sister, Princess Galyani Vadhana, at a State Dinner in Bangkok. Jamie McKeever (Music Director) and Eliah Seton (General Manager) were tasked with presenting her with gifts after their performance. The monarchy’s representatives coached them in painstaking detail with regard to how they must present the gifts: to approach the dais very slowly only once beckoned by the Princess, to bow before and after presenting the gifts, and to walk backwards when leaving the dais so as to avoid turning their backs to her (this was the most important thing to remember).

After their concert, which they closed with Blue Day, which Daniel Pearle (Assistant Musical Director) had taught them during the previous stop in Hong Kong, it was time for the gift-giving. Eliah reports:

“Certain that any mistake would land us in a windowless cell somewhere, I naturally met all the specific requirements of protocol and successfully presented the Princess with our album, A Rambling Notion, on a silver tray.

When I returned to the stage, it was Jamie’s turn. As if acting in political protest, he stumbled down to the dais, dropped a bouquet of flowers in front of the Princess which knocked over a glass, then waved to the affronted guests, turned his back and returned to the stage.”

When the King passed away in 2016, the Kroks were reminded of his history in Cambridge. He was born at Mount Auburn Hospital on December 5, 1927 while his father, Prince Mahidol, was a student at Harvard Medical School. King Bhumibol Adulyadej Square, between the Charles Hotel and the Kennedy School, was dedicated on April 8, 1990 by her Royal Highness Princess Chulabhorn and serves as a reminder of the close ties between the people of Cambridge and the People of Thailand. For several nights after his passing, candlelight vigils were held at this impromptu shrine.

From the recollections of Fred Ford, Rick Pepin, Allen Burns, Eliah Seton and Steve Dostart

Obituary

King Bhumibol Adulyadej is followed by Queen Sirikit (second from left) and Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn (left) as he leaves a hospital in 2011.

King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand, who took the throne of the kingdom once known as Siam shortly after World War II and held it for more than 70 years, establishing himself as a revered personification of Thai nationhood, died on Thursday in Bangkok. He was 88 and one of the longest-reigning monarchs in history.

The royal palace said he died at Siriraj Hospital but gave no further details.

King Bhumibol was a unifying figure in a deeply polarized country, and his death cast a pall of uncertainty across Thailand, raising questions about the future of the monarchy itself.

The military junta, which seized power in a coup two years ago, derives its authority from the king. But the king’s heir apparent, Crown Prince Vajiralongkorn, seen by many as a jet-setting playboy, is not held in the same regard as his father.

King Bhumibol spent most of his final years in a hospital, ensconced in a special suite. His portrait hung in almost every shop, and as his health declined, billboards proclaimed “Long Live the King,” signaling widespread anxiety about a future without him. In response, he openly fretted about the people feeling so insecure.

Thais came to see this Buddhist king as a father figure wholly dedicated to their welfare, and as the embodiment of stability in a country where political leadership rose and fell through decades of military coups.

His death ends a reign of 70 years and 126 days, one that few monarchs have matched for longevity. Queen Elizabeth II, by comparison, has ruled Britain for more than 64 years, having surpassed Queen Victoria’s mark in 2015. With King Bhumibol’s death, she becomes the world’s longest-reigning monarch.

King Bhumibol (pronounced poo-me-pon) was an accidental monarch, thrust onto the throne at 18 by the violent death of his older brother in 1946. He fully embraced the role of national patriarch, upholding Thailand’s traditions of hierarchy, deference and loyalty.

Western stereotypes of his country irked him. He disdained the Broadway musical “The King and I,” with its roots in his grandfather’s court. And, like a stern father, he was quick to chastise his fellow Thais when he saw the need.

In the king’s own book “The Story of Tongdaeng” (2002), about a street dog he had adopted, the message — there was always a message in his writings — was that affluent Thais should stop buying expensive foreign breeds when there were so many local strays to save. The book was a Thai best-seller.

If he was a people’s king, Bhumibol was a quiet and somewhat aloof one. He was a man of sober, serious mien, often isolated in his palaces, protected by the most stringent of lèse-majesté laws, which effectively prevent almost any public discussion of the royal family.

But he had a worldly bent. Born in Cambridge, Mass., where his father was a student at Harvard, he was educated in Switzerland, spoke impeccable English and French, composed music, played jazz on the clarinet and saxophone, wrote, painted, took up photography and spent hours in a greenhouse at his Chitrlada Palace in Bangkok.

Once he had returned from Europe, however, he stayed put. Never interested in a jet-set life, he stopped traveling abroad, saying there was too much to do at home. He was content to trudge through croplands in distant provinces in an open-neck shirt and sport coat, tending to the many development projects he encouraged and oversaw: milk-pasteurizing plants, dams that watered rice fields, factories that recycled sugar-cane stalks and water hyacinths into fuel, and countless others.

In a political crisis, Thais admired him for his shrewd sense of when to intervene — sometimes with only a gesture — to defuse it, even though he had only a limited constitutional role and no direct political power.

“We are fighting in our own house,” he scolded two warring politicians he had summoned to sit abjectly at his feet in 1992. “It is useless to live on burned ruins.”

Eleven years earlier, he had aborted a coup by simply inviting the besieged prime minister, Prem Tinsulanonda, to stay at a royal palace with the king and queen.

Prince Bhumibol in 1935 with his older brother, Ananda, at right, who was king of what was then known as Siam. Credit Associated Press

Thailand was transformed during his reign, moving from a mostly agricultural economy to a modern one of industry and commerce and a growing middle class. He presided over an expansion of democratic processes, though it was halting. He witnessed a dozen successful military coups and several attempted uprisings, and in his last years, his health failing, he appeared powerless to stem sometimes violent demonstrations, offering only vague appeals for unity and giving royal endorsement to two coups.

Meanwhile a strain of republicanism emerged as the country broke into two camps: on one side, the establishment, with the palace at its core; on the other, the disenfranchised, whose demand for a political voice threatened the traditional order.

Between them was the king, a calming symbol of unity — so much so that at times he wanted to moderate the country’s almost obsessive veneration of him.

In his annual birthday address in December 2001, King Bhumibol said, “There is an English saying that the king is always happy, or ‘happy as the king’ — which is not true at all.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/14/world/asia/thai-king-bhumibol-adulyadej-dies.html