2010 Proclamation for Frank Cabot

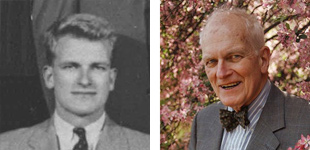

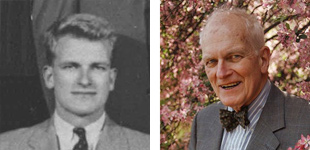

Francis H. Cabot, a financier and self-taught horticulturalist who created two of the most celebrated gardens in North America and helped preserve scores of others, died on Nov. 19 at his home in La Malbaie, Quebec. He was 86.

Francis H. Cabot, a financier and self-taught horticulturalist who created two of the most celebrated gardens in North America and helped preserve scores of others, died on Nov. 19 at his home in La Malbaie, Quebec. He was 86.

The cause was idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, his son, Colin, said.

In 1989, Mr. Cabot founded the Garden Conservancy, a nonprofit organization based in Cold Spring, N.Y., that works to preserve America’s most extraordinary private gardens.

Mr. Cabot was a hands-on horticulturalist — the magazine House Beautiful once described him as being “as likely to be wearing dungarees with kneepads strapped on and pruning shears holstered in the back pocket as he is a blazer and bow tie” — who built two extraordinary gardens himself.

The first, Stonecrop Gardens, is in Cold Spring, 55 miles north of Midtown Manhattan, on the property where Mr. Cabot and his wife made their home from the 1950s to the early ’90s. Now open to the public from April to October, Stonecrop features 12 acres of woodlands, grasses, bulbs, alpine plants and rock gardens.

The second, Les Quatre Vents (the Four Winds), is on his family’s estate in La Malbaie, beside the St. Lawrence River. Open four days each summer, it covers more than 20 acres and is widely considered one of the most ambitious private gardens in North America, if not the world.

Mr. Cabot’s book about his cultivation of that garden for decades, “The Greater Perfection: The Story of the Gardens at Les Quatre Vents,” was published in 2001.

A son of the New York branch of one of Boston’s storied families, Francis Higginson Cabot Jr., familiarly known as Frank, was born in Manhattan on Aug. 6, 1925. After serving with the Army occupation forces in Japan at the end of World War II, he received a bachelor’s degree from Harvard in 1949.

Mr. Cabot began his career as an executive assistant at Stone & Webster, the engineering and investment banking company of which his father was a vice president.

He became a partner at Train, Cabot & Associates, an investment and venture capital concern, in 1959. He became a gardener, he said afterward, to relieve the pressures of venture capitalism.

“I was a good promoter,” Mr. Cabot told The Courier-Journal of Louisville, Ky., in 2003. “But I was a good promoter of ventures that didn’t always work out. So I threw myself into gardening.”

In the late 1980s Mr. Cabot, by then a consummate plantsman, visited Ruth Bancroft, renowned in horticultural circles for the “dry garden” — thousands of cactuses, succulents and shrubs — she began in the 1950s on her property in Walnut Creek, Calif.

By the time of his visit, Mrs. Bancroft was in her early 80s. Worried that her garden would die with her, Mr. Cabot founded the Garden Conservancy.

To date, the organization has helped preserve more than 90 gardens, including those of the Longue Vue House and Gardens in New Orleans, ravaged by Hurricane Katrina, and the gardens of Alcatraz, which were tended by prison inmates and their guards for more than a century.

The conservancy’s inaugural project, the Ruth Bancroft Garden, continues to thrive and is now open to the public year-round. (In this case, at least, Mr. Cabot’s preservationist zeal may have been a trifle premature: Mrs. Bancroft, now 103, still lives on the property.)

Mr. Cabot, who retired from Train, Cabot in 1976, was chairman of the New York Botanical Garden from 1973 to 1976. His other horticultural posts include distinguished adviserships to the Brooklyn Botanic Garden and the Royal Botanical Gardens in Burlington, Ontario.

Besides his son, Mr. Cabot is survived by his wife, Anne Perkins Cabot, whom he married in 1949; two daughters, Currie Barron and Marianne Welch; nine grandchildren; and five great-grandchildren. An admirer of fauna as well as flora, he also had homes on a sheep station in Manapouri, New Zealand, and in Loudon, N.H.

At Les Quatre Vents, after members of the public had navigated its lawns, meadows, streams, hedges and woodlands; traversed its Nepalese rope bridges over lush ravines; admired its riotous floral displays (including 10-foot-high delphiniums and Himalayan blue poppies, no mean feat to coax from North American soil); explored its Japanese garden — and its white garden, rose garden, rock garden, shade garden and kitchen garden; lingered at its reflecting pools, waterfalls and lily ponds; walked round its pavilions, sculptures and topiary; and paused before its massive outdoor oven and ornate, towering “pigeonnier,” as Mr. Cabot’s dovecote is known, they were sometimes surprised, at journey’s end, to encounter Mr. Cabot.

He invariably had a question: Had they found their odyssey emotionally exhausting?

Those brave enough to answer yes were met with a characteristic reply.

“Good,” said Mr. Cabot, genuinely gratified.

A version of this article appears in print on November 28, 2011, on Page B9 of the New York edition with the headline: Francis H. Cabot, 86, Dies; Created Notable Gardens.

The cause was idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, his son, Colin, said.

In 1989, Mr. Cabot founded the Garden Conservancy, a nonprofit organization based in Cold Spring, N.Y., that works to preserve America’s most extraordinary private gardens.

Mr. Cabot was a hands-on horticulturalist — the magazine House Beautiful once described him as being “as likely to be wearing dungarees with kneepads strapped on and pruning shears holstered in the back pocket as he is a blazer and bow tie” — who built two extraordinary gardens himself.

The first, Stonecrop Gardens, is in Cold Spring, 55 miles north of Midtown Manhattan, on the property where Mr. Cabot and his wife made their home from the 1950s to the early ’90s. Now open to the public from April to October, Stonecrop features 12 acres of woodlands, grasses, bulbs, alpine plants and rock gardens.

The second, Les Quatre Vents (the Four Winds), is on his family’s estate in La Malbaie, beside the St. Lawrence River. Open four days each summer, it covers more than 20 acres and is widely considered one of the most ambitious private gardens in North America, if not the world.

Mr. Cabot’s book about his cultivation of that garden for decades, “The Greater Perfection: The Story of the Gardens at Les Quatre Vents,” was published in 2001.

A son of the New York branch of one of Boston’s storied families, Francis Higginson Cabot Jr., familiarly known as Frank, was born in Manhattan on Aug. 6, 1925. After serving with the Army occupation forces in Japan at the end of World War II, he received a bachelor’s degree from Harvard in 1949.

Mr. Cabot began his career as an executive assistant at Stone & Webster, the engineering and investment banking company of which his father was a vice president.

He became a partner at Train, Cabot & Associates, an investment and venture capital concern, in 1959. He became a gardener, he said afterward, to relieve the pressures of venture capitalism.

“I was a good promoter,” Mr. Cabot told The Courier-Journal of Louisville, Ky., in 2003. “But I was a good promoter of ventures that didn’t always work out. So I threw myself into gardening.”

In the late 1980s Mr. Cabot, by then a consummate plantsman, visited Ruth Bancroft, renowned in horticultural circles for the “dry garden” — thousands of cactuses, succulents and shrubs — she began in the 1950s on her property in Walnut Creek, Calif.

By the time of his visit, Mrs. Bancroft was in her early 80s. Worried that her garden would die with her, Mr. Cabot founded the Garden Conservancy.

To date, the organization has helped preserve more than 90 gardens, including those of the Longue Vue House and Gardens in New Orleans, ravaged by Hurricane Katrina, and the gardens of Alcatraz, which were tended by prison inmates and their guards for more than a century.

The conservancy’s inaugural project, the Ruth Bancroft Garden, continues to thrive and is now open to the public year-round. (In this case, at least, Mr. Cabot’s preservationist zeal may have been a trifle premature: Mrs. Bancroft, now 103, still lives on the property.)

Mr. Cabot, who retired from Train, Cabot in 1976, was chairman of the New York Botanical Garden from 1973 to 1976. His other horticultural posts include distinguished adviserships to the Brooklyn Botanic Garden and the Royal Botanical Gardens in Burlington, Ontario.

Besides his son, Mr. Cabot is survived by his wife, Anne Perkins Cabot, whom he married in 1949; two daughters, Currie Barron and Marianne Welch; nine grandchildren; and five great-grandchildren. An admirer of fauna as well as flora, he also had homes on a sheep station in Manapouri, New Zealand, and in Loudon, N.H.

At Les Quatre Vents, after members of the public had navigated its lawns, meadows, streams, hedges and woodlands; traversed its Nepalese rope bridges over lush ravines; admired its riotous floral displays (including 10-foot-high delphiniums and Himalayan blue poppies, no mean feat to coax from North American soil); explored its Japanese garden — and its white garden, rose garden, rock garden, shade garden and kitchen garden; lingered at its reflecting pools, waterfalls and lily ponds; walked round its pavilions, sculptures and topiary; and paused before its massive outdoor oven and ornate, towering “pigeonnier,” as Mr. Cabot’s dovecote is known, they were sometimes surprised, at journey’s end, to encounter Mr. Cabot.

He invariably had a question: Had they found their odyssey emotionally exhausting?

Those brave enough to answer yes were met with a characteristic reply.

“Good,” said Mr. Cabot, genuinely gratified.

A version of this article appears in print on November 28, 2011, on Page B9 of the New York edition with the headline: Francis H. Cabot, 86, Dies; Created Notable Gardens.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.