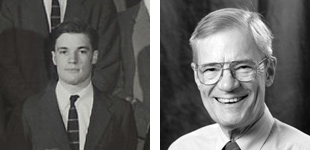

A National Book Award-winning historian and beloved professor of history and African-American studies at the University of Mississippi, Win Jordan died of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, at his home in Oxford, Mississippi on Feb. 23, 2007. He was 75.

The Kroks were enough of an influence on Win’s early career that he thought to mention us in an autobiographical essay posted on the website History News Network: “My distinguished medical career ended when as a college sophomore I got a D- in Chem 1A…. I spent nearly as much time singing with the Harvard Krokodiloes as going to classes.”

Fred Heller ’54 remembers Win as a happy-go-lucky and reliable Krok (perhaps too reliable, his teachers might have argued). After a stint in business and teaching at the high-school level, Win achieved a master’s degree in history from Clark University in 1957 and a Ph.D. in history from Brown University in 1960. The son of a history professor, Win quickly rekindled the family intellectual passion and became obsessed with the topic of race relations in the United States. “At that time (the latter 1950s) the field of history was still dominated by my fellow male WASPS.” Win wrote. “In the 1960s I enthusiastically welcomed signs of broadening in the profession and especially the slackening of the outrageous, falsely genteel anti-Semitism that had sapped the moral integrity of the old establishment. For my Ph.D. dissertation, I chose a subject that I thought of as a study of an old culture which was still imposing a crushing weight on the nation’s publicly stated political and moral ideals. More particularly, I aimed to understand the large component of emotion and indeed irrationality that characterized the attitudes of the white majority toward ‘Negroes’ in this country.” He credited his mother’s family’s Quaker abolitionist tradition in helping shape his interest, and in terms of prose style, “My exposure to the barbarous prose of the social sciences led to a determination on my part to write in language that at least attempted a measure of grace and clarity. ”

That quest eventually led to the publication of his seminal book White Over Black (1968), which is still considered one of the first major works of scholarship to delve into the causes of twentieth century racial inequality, with particular attention to its origins in the collective ethos of the early European settlers of North America. The book won four national prizes, including a National Book Award and one of his eventual two Bancroft Prizes. As part of its fiftieth anniversary, American Heritage magazine ranked White Over Black as the second-best book of all time in African-American history, second only to W.E.B. DuBois’s Souls of the Black Folk. Win’s second Bancroft was for Tumult and Silence at Second Creek: An Inquiry Into a Civil War Slave Conspiracy (1993).

In his review for The New York Times Book Review, historian C. Vann Woodward wrote that White Over Black “is a massive and learned work that stands as the most informed and impressive pronouncement on the subject yet made.” Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust, reviewing Tumult and Silence at Second Creek, wrote that Professor Jordan “has written a work of historical scholarship that leaves its scaffolding standing and visible, a study in which the process of discovery is at least as important as the result.”

Win taught at U. C. Berkeley from 1963–1982 and then accepted a post at the University of Mississippi, where he remained until his retirement in 2004. His students honored the event with the publication of an anthology of essays called Affect and Power: Essays on Sex, Slavery, Race, and Religion in Appreciation of Winthrop D. Jordan. In its introduction, Sheila L. Skemp described Jordan’s impact on his students: “No matter how relevant his own work is, Jordan never allows his own political or ethical agenda to interfere with his reading of the sources, and he urged his students to put their own preconceived notions aside as well. When their work led them in new directions and they arrived, often despite themselves, at unexpected conclusions, no one was more delighted than Jordan to discover that common wisdom is neither infallible nor particularly wise.” Robert Haws, who chaired the Ole Miss History Department, called Win “the most distinguished faculty member ever” in the university’s history department. “Before he had turned 40, his scholarship had defined the entire field of general race relations and set the scholarly agenda for the study of race in American history for two generations of scholars.”

Win remained dedicated to the Kroks all his life. For research on a novel, Krok Peter Lerangis ’77 contacted him by phone and “all sense of nervousness over disturbing a Great Thinker immediately melted away. He was warm and funny and honest, and began sending me all kinds of recent material he’d written on the topic. I had no clue he was ailing at all.” Not long before Win’s death, his passion for his work remained fiery: “I hope soon to write about the modern social and scientific conceptualizations of ‘race,’” he wrote, “which has proven such an appallingly dangerous term that many critics want to ban the word itself and to claim, mistakenly, that it is totally foreign to natural science including evolutionary biology. For present purposes I will merely emphasize that human beings constitute a single entity, whether it is called a single species, a breeding population, a gene pool, children of God, or the family of man. I personally find great value and aptness in all these designations. My doubts arise only in regard to the second term in the species name, Homo sapiens.”

Amen.

We miss you, Professor.

– Peter Lerangis H1977 – K1975, K1976, K1977

Winthrop D. Jordan died in his home in Oxford, Mississippi, on February 23, 2007, of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease. His White Over Black, which won both the National Book Award for history and biography and the Bancroft Prize, literally changed the way that historians have approached and understood the history of slavery and race in America. He won a second Bancroft Prize for Tumult and Silence at Second Creek: An Inquiry into a Civil War Slave Conspiracy.

Winthrop Jordan was born on November 11, 1931, in Worcester, Massachusetts, the son of Henry Donaldson Jordan, professor of history at Clark University, and Lucretia Mott Churchill, a direct descendent of abolitionist and feminist Lucretia Mott. When he entered Harvard University in 1950, he was determined to emulate his grandfather who was, as Jordan put it, a “real doctor.” Less than stellar grades in chemistry made him rethink that goal. But he did not turn immediately to the study of history. Indeed, he did not take a single history course as an undergraduate. He majored in “social relations,” where, fortuitously, he first encountered scholars who studied race in something approaching a systematic fashion. After graduating from Harvard in 1953, he floundered a bit, becoming a “management trainee” at the Prudential Life Insurance Company. Finding nothing about this job especially appealing—except for the subway rides to and from work, which allowed him much time to read and think—he accepted a job as an instructor of history at Phillips Exeter Academy. He earned a master’s degree in colonial American history from Clark University in 1957 and a PhD in history from Brown University in 1960. He was a fellow at the Institute for Early American History and Culture, in Williamsburg, Virginia, before joining the faculty of the University of California at Berkeley in 1963. Jordan remained at Berkeley for nearly 20 years, surviving the days of the turbulent Free Speech Movement, and serving as an associate dean for minority group affairs in the graduate school. In that capacity, he bailed students out of jail, tried to mediate the differences dividing administration from students, and became a friend and supporter of countless students who would have simply given up had he not intervened.

Win Jordan left Berkeley in 1982, joining the University of Mississippi faculty. There, he was an F.A.P. Barnard Distinguished Professor and Professor of Afro American Studies. In 1993, he became the first holder of the William F. Winter Professorship in History. He retired from the university in 2003. He received word that he had been awarded the B.C.C. Wailes Award from the Mississippi Historical Society just a few weeks prior to his death.

It is impossible to sum up Win Jordan’s contributions to the profession of history. His magisterial White Over Black alone made him an internationally known scholar. Elegantly written, breathtaking in its scope, it became—and remains—the starting place for anyone who wanted to examine the meaning and origins of race in America. Written at a time when “women’s history” was scarcely a dream and gender studies had not even appeared on the horizon, his analysis of the connection between race and sexuality in America was truly remarkable. He did not, of course, know about DNA, but his insistence—after a meticulous examination of the facts—that it was at least possible, even probable, that Thomas Jefferson was the father of some of Sally Hemings’s children, made him rather singular in the 1960s, even though it puts him in the mainstream today.

For his students, Jordan was not just a scholar and a teacher, but—as one student put it—”a north star” whose impact on every one of them remains deep and personal. The fact that so many of his students traveled to Oxford from all parts of the United States in order to attend his memorial service speaks volumes. They have also established a scholarship fund in his name, to help graduate students at the University of Mississippi with their research expenses. Jordan attracted a diverse and talented group of graduate students, who have published on topics ranging from the 17th to the 20th century, from Puritan New England to jazz musicians. Jordan never asked his students to be mere clones of himself. He urged them to find their own voice, their own passions, and to do what they loved to do as well as they possibly could.

When students first encountered a “Jordan seminar” they were often bewildered. He listened more than he talked, puffing quietly on his corn cob pipe, asking a question here and there, gently probing, prodding, pushing in what seemed to many to be a highly idiosyncratic way. All his students remarked on his wry humor and his laser-sharp intellect. Each class was different; each took on a life and character of its own. Students whispered anxiously among themselves, wondering what he “wanted” and what they were supposed to do. They soon found out.

He wanted correct grammar and word usage in their papers. If he did not get what he expected on the first draft, he demanded a second or even a third. He relegated “theory” and historiographical debates to the back seat and focused on a rigorous attention to the sources. He taught his students to listen to the voices of the past, to be open to any possibility, to avoid coming to conclusions too early, and to forget about their own personal or political agendas as they discovered—again and again—that common wisdom might be common, but it was not invariably right.

Win was a very special colleague. As a Quaker, he was not one to stand on ceremony, and was averse to anything approaching ostentation. Thus he arrived for lunch every day carrying a little brown paper sack from Ace Hardware Store. He used the same sack every day until it was literally worn out, which would lead him back to Ace to buy another screw or bolt, and thus to get another “free” sack. While some academic stars tend to avoid the scut work that makes any university tick, Win was happy to do his part. He was especially proud of his chairmanship of the University of Mississippi Faculty Traffic Ticket Appeals committee, an assignment that most people avoided assiduously, but which he saw as the price of admission to academia. He came to every department meeting and spoke rarely, but he always had something to say when he did. A “friend” as well as a Friend, he often greeted colleagues with small gifts or notes that marked no special occasion. He loved playing practical jokes on his colleagues, the more intricate and outlandish, the better. And despite his New England reserve and his obvious erudition, he loved what some might call “fourth-grade humor,” especially puns.

Jordan was married twice. His first marriage, to Phyllis Henry, ended in divorce. He married Cora Miner Reilly, a native Mississippian, in 1982. He is survived by Cora, his brother Edwin, three sons from his first marriage, and three stepchildren. As a scholar, teacher, and human being, he can never be replaced.

—Sheila Skemp, University of Mississippi

https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/may-2007/in-memoriam-winthrop-d-jordan

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.